Internet Book Club: The Modem World

A look at online communities before 'The Internet'

Previously in Internet Book Club:

The internet is a social place. We video chat with family, we watch livestreams and form parasocial relationships, we debate politics with complete strangers, and we connect with others in countless ways. But how did social connections work in the very earliest days of the internet? That’s the question The Modem World seeks to answer.

Kevin Driscoll’s book is about the pre-history of the internet, before it exploded into public consciousness around 1995. In fact, it’s not really about the internet at all - it’s about the precursors to the internet. Specifically, Driscoll documents in great detail the history of bulletin board systems. Bulletin boards stood in contrast to more formal precursors of the modern web such as ARPANET or USENET, which were mostly created, hosted, and used by universities and government agencies. BBSes were homebrew - created by hobbyists and maintained by hobbyists in loose and local networks. And while they were initially curiosities meant to pass along files and news updates, they soon found a new killer feature - community.

What the hell is a BBS?

The Modem World is a mixture of technical explanation and storytelling, because the story wouldn’t make much sense if you don’t know the details behind what a BBS actually is.

The first public BBS was built in 1978 in Chicago. It operated over your physical phone line, and to access it you needed a modem which could encode data over the phone line and in return decode data sent back.1 You’d instruct your modem to call a specific phone number (URLs were still more than a decade in the future) and your machine would then have access to the BBS.2 What did you have access to, specifically?

What you’d see was a primitive page by modern standards, but it was absolutely revolutionary at the time. The first BBSes were limited to text only - they were emphatically not html or the modern web. All inputs were through your keyboard, not a mouse. No sounds, no images, no color, no problem.

These BBSes had a few main functions. They had landing pages with instructions and announcements. They could store files and transmit them, making them repositories to spread software from. And crucially, users could read and write to the bulletin board. They could see what other users had posted to the bulletin board before them, then leave a new post or response that others would then read. The bulletin boards were by design temporary - the storage space on early BBSes was miniscule, so when the bulletin board reached its limit it would simply write over the oldest messages.

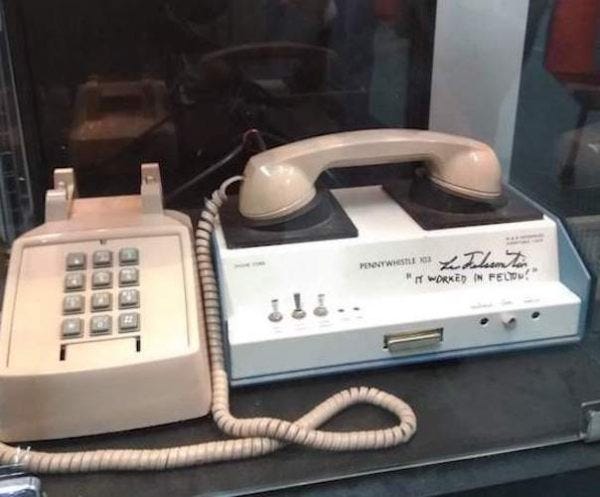

That was step one of the very first peer-to-peer networked communities. Step two was imposed by the economic realities of using contemporary phone systems. Long distance calling was very expensive3, and you paid by the minute for each minute you connected to the BBS server. So rather than pay outrageous fees to dial in to a single centralized hub, users organized dozens, then hundreds, then thousands and tens of thousands of local BBSes across the United States (and later, the world). A typical BBS would be centered in a specific geographic region - the image above is from a Chicago-based system. Its regular users were virtually all Chicagoans. Because of this local element, communities formed around local BBSes. Many of the users already knew each other socially or from local computing clubs, and BBS boards provided an easy and fun way to extend that sense of community.

Development and Decline

The book then takes us on a tour of the golden age of BBS servers. What started as a small number of BBS instances grew exponentially through the 1980s. Guides were published, modems got cheaper and faster, and more and more hobbyists began to set up their own bulletin board systems. BBS technology also advanced. Boards began to connect to one another, so that files and news could make their way through the entire BBS network. Boards were updated to allow for multiple phone lines to connect at once, to allow for email, to allow for color and images. Boards often separated into different ‘channels’ to allow for discussion on different subjects to be segregated. Connection speeds got faster, enabling more content and larger files to be shared.

But through it all, community remained the killer app for BBS boards. Magazines did surveys of computer nerds’ favorite BBS systems, and were shocked when readers voted without regard to how many files could be uploaded from each BBS, or the options and technical information available. Instead, they voted almost entirely based on which boards had the best communities. It took a while for people to realize how powerful online communication was. Computers, to that point, had traditionally been thought of as utilities, as calculating machines. They were tools to be used for a task, not a general purpose machine built to connect people. But once people realized that connecting with other people was possible, it quickly became the most important thing they could do on these home brewed micro-internets. That’s always been what I find most fascinating about technology - how it changes our interactions with other people.

In a precursor to the modern internet, communities could form around anything. Most communities were local in scale due to the challenges involved with long distance calling (even though networked relays made it feasible to communicate files and text to far away places). Some BBSes were just extensions of local clubs in the geographic area. Some were focused around particular topics, such as the famous Bay area BBS The WELL4 which was powered by Grateful Dead fans. Some focused heavily on nerd culture, computer discussion, or other tech subjects. Some were heavy on political discussion, and some were explicitly for gay and lesbian users. These boards were almost exclusively filled with nerdy white men - women and minority users existed, but it was common knowledge that they were severely outnumbered.

This pre-internet social networking introduced many of the identifiable features of today’s web. Why do Discord and Slack have different ‘channels’ for discussing different topics? BBSes did it first. Many sites allow you to use a fully anonymous or pseudonymous handle that persists over time. BBSes invented that. Avatars? ASCII text art? Emojis? Peer-to-peer media piracy? Direct messaging? Username registration? Crowdfunded free-to-use products? Copyright disputes? Interactive games? Internet lingo? Moderation policies and user bans? All pioneered in BBS communities.

And yes, because it’s the online world, there was porn. As connection speeds improved and it was easier to share image files, porn grew rapidly. The first ever digital porn business was literally a guy scanning physical pictures from magazines, digitizing them, and selling access to those images on his BBS server. The internet had porn before it was even the internet.5

BBSes expanded rapidly through the entirety of the 1980s and into the 1990s. By some estimates, there were hundreds of thousands of local BBS boards in the early 90s. And then suddenly it all came crashing down.

The widespread adoption of the modern World Wide Web6 by 1995 was an extinction level event for BBS systems. Technology moved fast enough that bulletin board systems simply got overtaken. URLs for websites replaced phone numbers for BBS servers. HTML based websites with their images, graphic design, and clickable hypertext links were far more appealing to new users than the traditionally text-only BBS boards. Mouse-based graphical user interfaces were more intuitive than text-based command systems. And the technology involved in connecting to the internet was more global in scale, with no concerns that connecting to the wrong website would see you rack up long distance calling charges. The modern web literally decimated7 BBSes in its first year of existence, and by 1997 BBS activity had dropped to less than a third of its 1994 peak. Some BBSes transitioned to becoming websites with modern URLs and web pages. Some actually became local ISPs, becoming the technical gateway for their users to connect to the wider internet. Some simply shut down and died. The peer-to-peer hacked together nature of BBS servers was in terminal decline, never to recover. The ‘Modem World’ was finished.

Lessons from the Modem World

I enjoyed The Modem World, even though its subtitle A prehistory of social media isn’t quite accurate.8 Frequent readers will be aware that I’m fascinated not by the technology involved in the internet, but by how people use that technology to talk with each other, fight with each other, form groups, create trends… basically, how they act as people in the digital systems we’ve created. Driscoll’s book is a good look into how people interacted with each other in some of the very earliest online systems.

The book has a number of strengths. It strikes a balance between explaining the technology and explaining the culture. It has a narrow focus but that works to its benefit - books on internet topics tend to spiral outwards and lose focus, and Driscoll never does. And it does a great job explaining the motivations behind the creation of these hobbyist groups and how the developed into real communities. It’s a great piece of historical reporting.

It also has a few weaknesses. I’d love to have seen at least a little bit of discussion of USENET and similar networks, even if they weren’t the focus of the book. I’d also love to see more of the ‘common user’ experience, as the book is mostly reporting from the perspective of the sys-ops who managed BBSes. At times the book could have dived deeper into what everyday discussions and usage actually looked like. But despite these weak points, the book overall is quite good.

The beautiful thing about humanity is that no matter what the circumstances, we’re always building communities. We’re always talking, debating, fighting and loving. That’s true in times of peace and times of war, when we’re close and when we’re far, when we’re in person and when we’re staring at a screen. We are inherently tribal animals, and we’re always looking to build a tribe of like minded souls to connect with. That was true of the Modem World, and it’s true in today’s social media. I would recommend The Modem World to anyone interested in the pre-history of online communities.

Fun fact: The word ‘modem’ is a portmanteau of MODulator-DEModulator for the encoding/decoding work a modem does.

Unless someone else was on the line, in which case you’d get a busy signal and have to wait for them to hang up.

For the tragically young - you used to be charged by the minute for phone calls, and long distance calls were charged at far higher rates than local calls within your area code. Yes, this is ancient history as told to you by a boomer.

Acronym for ‘Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link’

It also had Nazis, although the book claims their early presence on BBSes was marginal at best.

Which in a technical sense is not a synonym for ‘internet’, even though we functionally use it that way.

Literally! Decimate as in ‘to reduce by 10%’

The book, as explained, focuses entirely on Bulletin Board Systems. A true prehistory of social media would need to include USENET and other similar pre-internet networks, which also innovated much of what social media is today.

Does recommending this book to you obligate me to upgrade my subscription? 😀

https://x.com/TDMix/status/1744734504101797900?t=9je0xoQuvVMs_mr2_OBD2g&s=19

Seriously, if X was all about sharing recommendations on obscure history of computing books I'd spend all my time there...

I must note that I and about 50-100 active posters are still keeping one of the big 90s BBSes, ISCA, up and running. It’s kind of delightful; a place where no matter what question you have, _someone_ knows the answer. Recommended for exploring, if you can find a telnet app: bbs.iscabbs.com, port 23. It’s not exactly high-scroll anymore, but still some fun people to talk to, at least if you like talking to middle-aged nerds.