Real Wars are now Flame Wars

Social media battles are now an integral part of modern day military conflict

Two days ago, the long-running conflict between Israel and Palestine once again turned hot. Hamas launched thousands of rockets at Israel and invaded Israeli territory, killing hundreds of civilians.

Normally, I would rather gargle a bag of diarrhea than write about the Israel/Palestine conflict on the internet. I’m not sure there’s any existing topic that’s as toxic, where expressing any opinion whatsoever leads to the nastiest fighting imaginable. But in watching the social media reaction to the conflict, I see important things to understand about how social media interacts with war1 and what it says about the nature of modern military conflict.

To set expectations: I am not going to comment, not even the slightest bit about who is right and wrong in the conflict, which actions are the most morally reprehensible, who is to blame for what, etc. This isn’t because I am uneducated on the topic or because I don’t have opinions. It’s because this is a blog dedicated to the analysis of social media and not geopolitics. There are better places for you to get geopolitical analysis and moral clarity than a blog that spends most of its time talking about Momfluencers, MrBeast and Lil Tay. By all means - go read as much analysis and history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict you want. But you’re not going to find it here.

I’m also not going to be linking very much. I normally use a very link-dense style that heavily references examples of what I’m talking about. But too much of this material is ghastly, gruesome and disturbing. It’s easily findable on your own if you want to find it, but I’m not going to link any of that here. With all that said, onto the interesting stuff.

The first thing I noticed - mere minutes after the first reports began to come in from Israel - was how fast social media turned from reporting to propagandizing. It could not have been more than five to ten minutes between the first news of the conflict and the first narratives being pushed, both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian. A real war was breaking out in front of our eyes thanks to the magic of the internet, and simultaneously a proxy war to control the messaging broke out between various camps on social media.

Look at this footage of a horrifying attack. Look how innocent this dead child is! Watch this brutal footage of a woman bleeding to death. Watch this video of a home invasion. Support our fight against these brutal, awful people. Stand with us. But wait - look at this deeper narrative. Look at this justification. Remember this other act, by the other party! Don’t forget what they did before, and how that never made the news! Read this history which supports my side’s actions. But read this rebuttal of that justification. Read this counter-rebuttal. The other side won’t tell you about this! Question whether that heart-wrenching picture or video was even accurately portrayed. But look at this new attack! This endless fight is playing out on Twitter, Reddit, Instagram, in countless Discord channels and Slacks, all across the web.

Watching this play out in real time, it struck me that we will likely never again experience a war without a corresponding social media battle for public opinion. This is now a permanent feature of modern conflict. Social media is just another combat zone, and often a crucial one. Posts are strategic assets. The discourse is a battlefield. All real wars are now Flame Wars.

Now, I’m exaggerating a bit here for effect. I don’t think it’s literally the case that every single war will feature prominent discourse. I’ll provide one counter-example to my thesis - the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflicts in the last few years. Whether we’re talking about the entire Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, or the recent Azerbaijani offensive in Artsakh, social media largely hasn’t mattered. Some conflicts are over too quickly for the discourse to matter. Some wars simply don’t interest the rest of the world, so it doesn’t matter what narratives emerge.

But for high salience or large scale conflicts, I think my thesis holds up. All wars will include flame wars. Partially, this is just a consequence of the nature of social media. The founding idea behind this blog is that Posting is the Most Powerful Force in the Universe, and that people simply cannot help themselves when it comes to posting. We’ve also talked about how social media structurally encourages both conflict and extremism. Given those ideas, it’s no surprise that major conflicts would lead to conflict online.

But this is also happening because public opinion really matters in these conflicts. Social media incentivizes conflict everywhere, but there are no real life implications for a Cardi B vs Nicki Minaj stan war. Most instances of The Discourse are petty nonsense that will be forgotten quickly and mean nothing. But for wars like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, public opinion is crucial. Consider the Ukraine-Russia war as an example of how much it can matter.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, the overwhelming response from the Western world was sympathy for the Ukrainian cause. That sympathy was, of course, partially the result of the actual circumstances on the ground. But it was also something that was actively contested on social media. Russia is known for their extensive social media operations which try to influence world politics. But Ukraine has also used a very savvy social media campaign during the war to garner support. Russia, despite their reputation for online troll farms and hacking, has mostly failed online.2 The vast majority of people looking at the conflict conclude that Ukraine is the party worth supporting.

This has enormous consequences. Foreign governments have donated more than $100 billion to fund Ukraine’s war effort. Ukraine winning the online battle for sympathy has been worth, at minimum, tens of billions of dollars in extra aid. Without the extensive sympathy, the amount donated would surely be much less. It’s plausible that winning the social media propaganda war is the reason Ukraine hasn’t collapsed outright as a country.

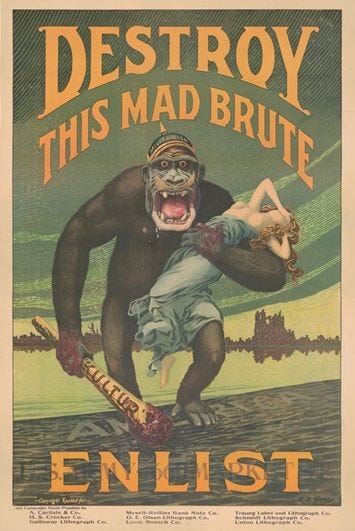

Propaganda has always been part of conflict. Yellow journalists blamed the explosion of the USS Maine on Spain. This was almost certainly not true, but it jump-started the Spanish-American War. World Wars 1 and 2 are famous for their patriotic posters denouncing the enemy and rallying the population to fight.

The second World War saw a real effort to begin spreading propaganda abroad, not just at home. Radio broadcasts targeting foreign populations became more common, and dropping leaflets over enemy territory was so popular that the US had a whole squadron of B-17 bombers devoted solely to dropping them. During the Vietnam War, Hanoi Hannah broadcast several radio segments a day meant to demoralize American troops. Radio Free Europe was a mainstay of the Cold War, as was Soviet funding of communist literature in capitalist countries.

Propaganda has always been around, but there are a few key differences between what happened then and what’s happening now. Social media and modern tech have utterly revolutionized the ways we communicate with each other around the world. It’s only natural that there’s been a corresponding change in how wartime propaganda is spread. I see three key differences between modern social media influence operations and previous wartime propaganda efforts:

Immediacy

It can’t be overstated how fast the social web moves. People on the other side of the world can know within minutes about the latest bombings, troop advances, and wartime updates. Information often flows so freely that OSINT has become one of the most important sources of wartime intelligence.

Importantly, this immediacy includes visual media in addition to text reporting. We’re getting horrifying videos of a building exploding. We’re seeing a death squad surround a house, enter, and kill everyone inside. We’re getting close up pictures of soldiers about to head into battle, of artillery firing, of dead children. Real time pictures and videos move just as quickly as text, and these videos can be heroic or horrifying, funny or devastating.

And wherever these images appear, the propaganda is right behind. Opinions can be formed within minutes of any particular incident. Countries don’t have days or weeks to craft narratives - they often don’t even have hours. Modern propaganda efforts move faster than they’ve ever moved.

Direct conflict

Previous generations would sometimes see one country’s propaganda clash with another country’s propaganda. That is, after all, the entire point of the exercise. But that conflict was normally at a distance. Warring pamphlets might dispute who was at fault, but those pamphlets were dropped on entirely separate populations. One country’s radio show might argue against a point made by another country’s radio show, but the participants weren’t on the air on the same program. They were having an argument separated by time and space, not directly in one another’s faces.

That, to put it lightly, is not how social media works.

Today’s narratives are battled over in real time in direct arguments. The people arguing for pro-Israel positions are responding directly to those arguing for pro-Palestinian positions. They’re fighting in long threads on Twitter, in news site comment sections, in subreddits and Discords and everywhere else. Propaganda in the old world was largely a one-way broadcast, and maybe every once in a while you’d have to respond to some argument the other guy’s one-way broadcast was making. Propaganda today is a real time, omnidirectional free-for-all with thousands of people duking it out, personally insulting and screaming at one another. The official foreign ministry of one country will do a dunking quote tweet of a different country’s foreign ministry. Never before have propaganda battles been so immediate and in-your-face. But that also leads into the last major difference…

Distributed Propaganda

Propaganda has, in past wars, almost always been something controlled by centralized powers. A government would craft a message. They’d spend significant resources to try to get that message in perfect form. They’d invest time to figure out which specific people they should target with the message, how they should be targeted, and when would be the best time to spread the message. They were in control from start to finish.

Today, propaganda starts online. Within minutes of a major development in a conflict, partisans are already crafting narratives meant to make their side look good and the other side look evil. The governments involved can influence this process. They can promote favored narratives and send signals about what to say and what not to say. But they sure as hell can’t control things overall. Most pro-Palestine posters have no connection to Palestine whatsoever, and are capable of creating pro-Palestine messages without any help from any Palestinian organizations. The same goes for pro-Israel posters, the majority of whom are not Israeli or Jewish. Even if there was a conflict where the official governments on both sides did zero propaganda work, tens of thousands of eager online posters would happily step in and do their work for them.

Propaganda today can’t be carefully crafted by a central authority. It’s created en masse by thousands and distributed chaotically. These people will use varying messages, varying tactics. Some of them will try for reasonableness, some will stoke anger. Some will appeal to logic, some will appeal to base emotions. Some will be restrained and some will be militant. And there’s not much you can do to stop them. They’ll test arguments, refine them, stick with some and abandon others. There are often dominant themes, but none of the posters have any obligation to stick to those themes. You can’t control online mobs even during the simplest of times or on the simplest of subjects, and you certainly can’t control them when it comes to highly charged matters of life and death.

What should we expect moving forward? Expect that all future wars that clear a certain level of size and profile will exhibit these dynamics. Modern propaganda is different from what we saw in previous generations. We should be aware that from the moment we find out about a conflict, we’re already being subjected to competing narratives about the conflict. And we’re not going to be passively consuming those narratives - we’re going to be in the middle on the fight watching our friends and acquaintances do active battle for control of the message. We’ll be surrounded by the screaming.

Governments are already adapting to this reality. We’re now seeing them seed their preferred narratives ahead of time, so that when the conflict does break out their thousands of online partisans know what to say. They’re growing savvier about influencing the domestic politics of other nations - this has been part of Russia’s playbook for years. Governments are learning how to flood the zone with shit. There are a lot of governments doing this stuff as we speak, but surprisingly they still have a great degree of trouble influencing more than the fringes - for now.

When I wrote The Internet is For Extremism, I summed up the post with this:

I wish I could leave you with some sage wisdom about What This All Means, or perhaps Where We Go From Here. I don’t really have that. I don’t think we can really change it or stop it from happening. This is just a consequence of how the social internet operates, and perhaps a consequence of human nature…

The only thing I can think to say is that it’s important we recognize this happening. If you recognize the phenomenon, you can stop yourself from being entirely sucked into it.

I think that message applies here as well. Social media has always metaphorically resembled a battleground, but it’s increasingly a real one with real stakes for real wars. There’s nothing you or I can do to interrupt this dynamic, but we can at least be aware of it as we watch it happen.

Or the resumption of hostilities in an old war, if you prefer

At least, in western countries. Some reporting points to Russian influence operations having more success in regions like Africa and Latin America.

I thought your post on Twitter, basically, that no one is required to post on this, you can absolutely refrain from posting if you have no idea what you are talking about, was spot-on, but the comments were about what you'd expect.