On June 25th, 2019, I donated a kidney. I had two kidneys going into that day; I have one kidney now. Yesterday marked my fourth anniversary of giving up that kidney. I didn’t donate to a person I know, but to a stranger on the kidney waiting list—a queue that, despite our ever-increasing medical mastery, remains depressingly long.

In the years since I’ve donated, I’ve become an advocate for this kind of living kidney donation. So I hope you’ll indulge me as today’s Infinite Scroll post goes in a different direction than our usual Very Online Content (which will be back soon, I promise). This morning, I’d like a share an article I wrote four years ago. It explains why I made this choice and makes the argument that you, the reader, should also consider donating one of your kidneys.

I’m also doing an informal Ask Me Anything Down in the comments. If you have any questions about my experience, about potentially donating your kidney, or kidney donation in general, please leave a comment! I’ll be responding to everything.

The basic argument can be broken down into three main points:

Kidney disease is a serious problem.

Living donations produce extremely large benefits to recipients.

Living donations are very safe for the donor.

Let me take each of these by turn.

Kidney Disease is a Serious Problem

In the United States, kidney disease is a silent epidemic. It kills three times as many people as all homicides put together. It kills more people than car crashes, breast cancer, or suicide. More than 100,000 people are currently on the kidney donation waitlist, constituting 83 percent of all people awaiting life-saving organ transplants. That’s not even counting the tens of thousands of individuals who could benefit from a donated kidney but haven’t joined the waitlist—no doubt a function of the queue being discouragingly long.

Despite this, kidney disease receives very little media coverage compared to the above issues.

On top of the raw death counts, life with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) is often short and awful. Dialysis is miserable and often steals your ability to lead a normal life. It’s a procedure that saps all your energy and takes three to four hours, and must be done three to four times per week, every week, or else you die (and it only replicates about 10 percent of normal kidney function). It’s hard to maintain a job, personal relationships, hobbies, or a normal life while on dialysis. Survival rates on dialysis are grim: 20–25 percent of patients die within a year, and only about 1/3 of patients will survive five years.

Living Donations Have Extremely Large Benefits For Recipients

The worst part is that, for so many, these deaths are completely preventable.

While there are some ESRD patients who are too old for surgery or too sick to help, the majority of ESRD patients can easily extend their lifespan with a donated kidney. Our best estimates show that tens of thousands of people die every year needlessly, when they could have been saved by a donated kidney.

Recipients who get kidneys from living donors tend to get more than 10 additional years on average, and that number has been increasing over time due to advances in medicine and treatment (living donations are also significantly better than kidneys from deceased donors, although both are good). That’s a lot of time—Matthews captured the importance of this consideration in his essay:

I went through a week of serious pain and a mild recovery thereafter, and as a result, someone got off dialysis and gets to enjoy another nine, 10, maybe more years of life.

These years aren’t empty years, either — they’re relatively healthy years, standing in stark contrast to the horror of dialysis. A typical living kidney donation will change a recipient’s life expectancy from “less than five, likely miserable, years” to “double-digit years, potentially decades, of mainly normal functioning and living.”

A summary of a report by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients explains why this high degree of optimism is warranted:

If you remove from consideration patients who died for reasons unrelated to graft failure, the half-life of a living donor kidney graft that survives past the first year post-surgery is 26.6 years.

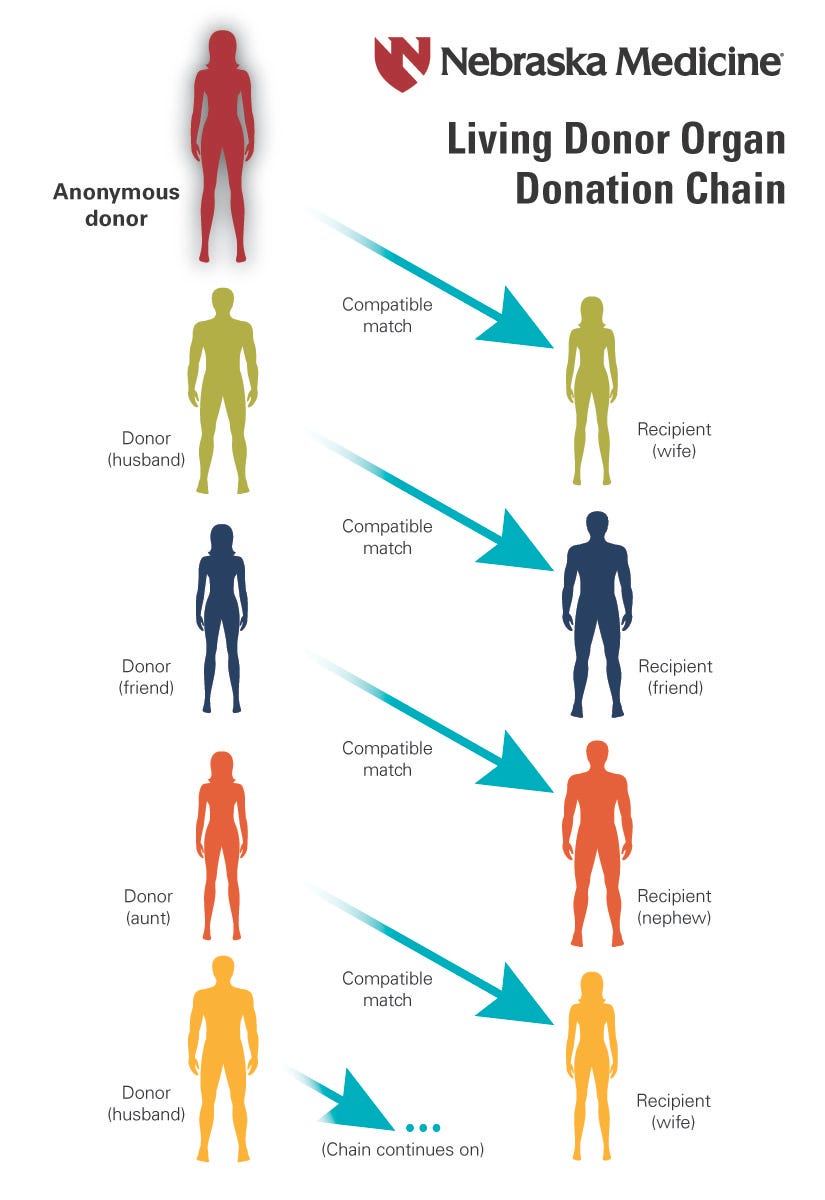

To add to the immediate benefit, living kidney donors who give a kidney to a stranger (what is sometimes called an undirected donation or an altruistic donation) can start kidney chains. Because kidneys require a biological match, recipients who need a kidney often have family members or friends willing to donate a kidney but unable to—since they are not a match. In a donation chain, an undirected donor can give a kidney to Recipient A, with the understanding that Recipient A’s family member of friend will then donate to someone else (Recipient B). Recipient B’s family member or friend then gets involved and donates to Recipient C, and so on.

Anecdotally, the average chain length seems to be about four or five, but there are some chains that reach dozens of donations and above. Donating altruistically doesn’t just add years to one recipient’s life, it can transform patients into recipients—without the chain starting they might never have become recipients in the first place—and thus add years to many recipients’ lives.

Living Donations Are Very Safe For The Donor

The benefits of living donation are clear. What about the costs to the donor?

Any major surgery involves risks and costs, and shouldn’t be taken lightly. But the risks from donating a kidney are relatively small, and the vast majority of donors experience no long-term impact on their lives.

Kidney donation has zero direct cost, and a small but potentially significant indirect cost. Direct costs are zero, because kidney donation surgery is 100 percent covered by Medicare and/or the recipient’s insurance. Indirect costs include potential lost wages from time off work — the average donation requires about two days in the hospital post-surgery, and two to four weeks off of work. A donor may also incur some travel or related indirect costs, although, increasingly, programs exist to cover these costs for donors. A new program initiated by the federal government will cover lost wages, travel costs, and child care expenses for donors.

There are also medical risks to donating one’s kidney, although the risks are quite small. The risks can be categorized into immediate and long-term risks. For donors who do not have high blood pressure, there’s a roughly 1 in 10,000 chance of death during operation (as a reference, this is lower than the rate of death during childbirth in the U.S.). This is the primary immediate risk, alongside the two-day hospital stay. There is also some risk for secondary issues post-surgery such as infection, fever, etc., but these risks are usually minor.

Long term, donors do see higher risk for kidney disease. But this risk is small in absolute terms — donors move from about a 0.1–0.3 percent chance of End Stage Renal Disease to about a 1 percent chance. The vast majority (99 percent) of kidney donors do not develop ESRD. For women who donate and may become pregnant in the future, donation also increases the risk of preeclampsia from 5 to 11 percent.

In short: some risks do exist, but they are relatively rare and minor in comparison to the benefit that kidney donation provides.

I had two life vests, someone was drowning without one, and it honestly cost me very little to give them my additional one. My life hasn’t really been impacted in any way in the four years since I donated.

I donated a kidney because there is an ongoing kidney disease crisis, and it’s a crisis we can fix. Donating is safe, it provides huge benefits, and it means I’m helping to fix a problem we know is fixable. There is no mystery about how to solve the kidney crisis — we know how. It’s only a political and moral failure that keeps the crisis going and people dying.

I hope this piece inspires you to consider becoming a donor. Donating is not the right choice for everyone, but it might be the right choice for you. There are only a few hundred altruistic donations each year in the United States, and more are desperately needed. If anyone is interested in learning more about the research around kidney donation, kidney policy, kidney charities, or the process of donating a kidney: please leave a comment and I’d be very happy to answer any questions you have.