Beware Your Audience

Influence an audience long enough, and the audience will begin to influence you

“Cause we all just wanna be big rock stars

And live in hilltop houses, driving 15 cars

The girls come easy, and the drugs come cheap

We'll all stay skinny, 'cause we just won't eat” - Nickelback

Let’s talk about fame

There are a lot of songs about wanting to be famous. There’s Mr. Jones by Counting Crows, Beverly Hills by Weezer, Forever by Drake, among countless others. But as much of a joke as they’ve become in the culture, my favorite has always been Nickelback’s Rockstar. It’s brutally honest - the protagonist doesn’t hide that he wants to be famous for entirely selfish, shallow reasons. He’s a vain prick who wants to fart out low-effort music and be rewarded with adoration, money, sex and drugs. It’s an incredibly self-aware song for Nickelback of all bands to have released.

They say that everybody wants to be famous, and the data bears it out. Surveys consistently find that social media influencer is among young Americans’ most desired careers - along with other fame heavy jobs like musician or actor. That’s not a new phenomenon, of course. For generations we’ve had aspiring actors moving to Hollywood, stage performers moving to NYC to shoot for Broadway, country music singers moving to Nashville, all chasing the dream of stardom. But the rise of social media has changed the nature of fame.

Industries like acting and music are sometimes called ‘superstar’ industries or ‘glamor’ industries. A tiny percentage of aspiring actors will become superstars, but most will end in total failure, waiting tables in Los Angeles and eventually dropping out of the industry altogether. That’s always been the deal - a very small chance at very big stardom.

But today, the entire economy of celebrity has been radically altered by the social internet. In the 1990s, getting your face in front of tens of thousands of people was an achievement reserved for a very few - in the movie Groundhog Day Bill Murray’s character considers himself a celebrity simply because he’s a weatherman on a local news channel. But since the rise of YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter, that level of micro-stardom is commonplace. On YouTube alone there are over 300,000 accounts with more than 100,000 subscribers, and on Twitter there are hundreds of thousands of accounts with over 10,000 followers.

What social media has created is effectively a middle class of fame.

Fame is now fractal. There are still nationally famous A-list celebrities. But there’s also an upper-middle class of online celebrities now, with hundreds of thousands of followers. There’s a middle class of internet fame composed of folks with tens of thousands of followers. And there’s even a lower-middle class consisting of people who aren’t really famous, but do have 5,000 or so followers. That audience size is more attention than they’d ever get in real life, and this kind of person will often have a few hit posts that have gone ‘viral’ for them. Lots of content creators are newly famous, for this new definition of fame.

Whether it’s thousands or millions, more people than ever are thinking about the audiences they have. And that can be dangerous, because people who get even a little bit of fame should be afraid of their audiences.

The Danger of Audience Capture

Let’s state something that’s very obvious - influencers have a lot of influence. These internet personalities are often able to persuade their audiences, whether they’re massively famous or just a little famous. But what we don’t think about enough is how much their audiences can influence them.

In his famous blog post Status as a Service, Eugene Wei — one of the most incisive analysts of social media systems — argues that the mass-marketing of a chance at micro-celebrity is actually a successful social network’s core business model:

Can I use the social network to accumulate social capital?…And how do I earn that status?…

Read Twitter today and hardly any of the tweets are the mundane life updates of its awkward pre-puberty years. We are now in late-stage performative Twitter, where nearly every tweet is hungry as hell for favorites and retweets, and everyone is a trained pundit or comedian. It's hot takes and cool proverbs all the way down.

He’s right. Twitter was originally imagined as a ‘microblogging’ site, where people would share passing thoughts and and snippets from their everyday lives. We forget that because almost nobody uses it that way any more. Now, we’re all tweeting to get attention, to get likes, to be the funniest and coolest personality, to go viral.

Remember, the new landscape of social media fame is that it’s fractal. People who reach 1000 followers tweet with the same sense of heady exaltation as those who reach 10,000 or 100,000. For most people, having a few thousand people read what they write is far more attention than they’ll ever get in their offline lives. Small scale virality is just as intoxicating as large scale virality.

And this brings me to the main point of this post, which is that social media influencers, if they’re not careful, can be manipulated by their audiences.

If you’ve amassed a following, you’ve probably got a niche of some kind. You’ve cultivated a specific audience based on your style of posting. Audience Capture is the phenomenon by which online personalities begin feeding audiences what they want to hear - and end up becoming beholden to them.

This is not necessarily as sinister as it sounds. Whenever influencers say something we like, we click the “like” button, or share it to our own followers. When we don’t like it, we ignore it or criticize it in the replies and comments. This is just social media’s equivalent of the Hayekian price mechanism — a distributed system of feedback that tells the take-generators which opinions are in demand. This is the marketplace of ideas, in a very literal sense. (Note: Whether you think this is a good way to organize sociopolitical discourse is another question entirely.)

We all want to go viral, and as status-seeking monkeys we’re all constantly searching for what can help us do that. The natural outcome of all this is that we end up posting what our followers want to hear - not what we actually think.

You make a provocative post on some topic, and get more likes and shares than you normally receive. You then make an even more provocative post, and it does even better. Social media is structurally set up to encourage extreme views and content, and before long you’re posting about this issue constantly. You never planned to become a rage-bait influencer on this particular topic, but the alternative is to go back to your posts getting a pitiful amount of engagement, and you’re not going to do that.

This temptation is especially strong in politics. Researchers have found that animosity towards political out-groups is a powerful driver of engagement on Facebook and Twitter:

Social media may be creating perverse incentives for divisive content because this content is particularly likely to go “viral.” We report evidence that posts about political opponents are substantially more likely to be shared on social media and that this out-group effect is much stronger than other established predictors of social media sharing, such as emotional language….Language about the out-group was a very strong predictor of “angry” reactions (the most popular reactions across all datasets).

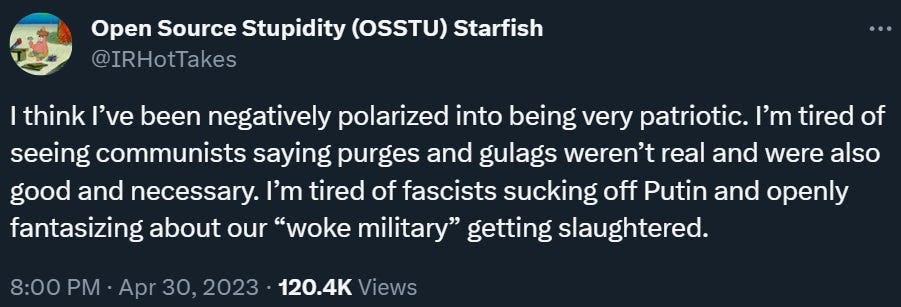

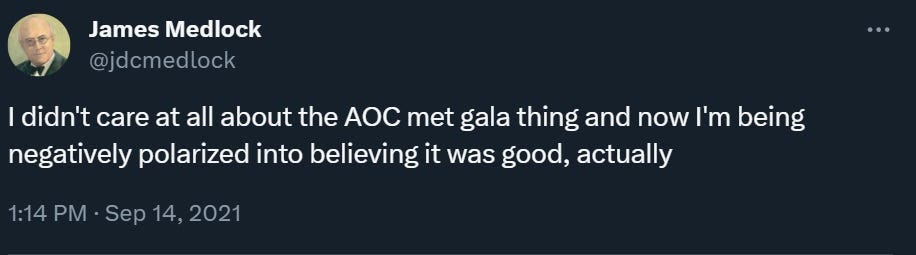

This audience capture phenomenon can even work in both directions. Outlandish hot takes can generate a lot of attention and engagement, and they can lock you into a cycle where you’re captured by your audience’s expectations for how you post. But they can also negatively polarize people against you. You don’t have to search far to find extreme takes polarizing normal people against whatever the take happens to be:

This sort of thinking is dangerous for anyone who values independent thought. You don’t want to end up with your political views defined by whatever gets you the most likes, or what you happen to have been negatively polarized against. But that’s increasingly common in today’s social landscape.

The most extreme cases of audience capture trend towards self-flanderization, where online creators become a parody of themselves. Consider the case of Nick Perry, aka Nikocado Avocado. Perry started his content career as a milquetoast vegan violin performer. But to his detriment, Perry tried doing a few mukbang videos where he would eat large meals of various foods. His audience loved them - and demanded more. Not just more mukbang content, but bigger meals, more extreme eating challenges. Perry took up the challenge and created the ‘Nikocado Avocado’ personality. The end result, a few years later:

I’m not sure there’s a better way to hammer home the point - following your audience’s cues blindly is actually dangerous. Beware your audience. They may like you, but they’re not necessarily good for you.

Kill Your Darlings

One of the classic pieces of advice for any writer is to Kill Your Darlings. Writers are often very proud and protective of parts of their work - a particularly clever turn of phrase, a certain character, a crazy plot twist. But good writing is usually concise, and good storytelling is usually direct. As a writer, you can’t get too attached to some very clever thing if it hurts the flow of your writing. You need to able to kill your darlings, no matter how proud you are of them.

Online content creators should view not just their content, but also their audiences, through the lens of ‘Kill Your Darlings’. Maybe your followers expect one thing from you. Maybe they’ll be bored or angry if you post in a different style, or with a different political slant. Maybe some will unfollow you!

Post how you want to post despite that. Make them angry. Kill your darlings, drive away the audience that’s trying to capture you.

But don’t take it from me. Listen to Bo Burnham, one of the most artistically gifted comedians in the world today. Near the end of his special Make Happy, in a section filled with silly jokes about Pringles and Chipotle burritos, he suddenly goes deep into his fear of the audience and how he feels stifled by their expectations: (starts at 5:00)

The truth is my biggest problem's you

I want to please you - but I want to stay true to myself

I want to give you the night out that you deserve

But I want to say what I think and not care what you think about it

A part of me loves you

Part of me hates you

Part of me needs you

Part of me fears you

And I don't think that I can handle this right now

I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a more painfully honest account of an artist grappling with audience capture. Burnham feels the pressure to give his paying audience what they expect, but still wants be his authentic self. And I think we could all learn something from him here.

You can respect your audience and be suspicious of them at the same time. You can try to give them want they want, but you also shouldn’t shy away from offending them. This applies to famous artists, but it also applies to micro-influencers. We’re all a little bit famous these days, and that means we’re all vulnerable to the dynamics of audience capture. So beware your audience.

Thanks to Noahpinion, who contributed to portions of this piece

That Nick Perry picture is one of the most depressing things I've ever seen. If there was a content creator who was continually cutting himself more and deeper for his followers, we'd be horrified as a society. And yet, isn't this the same thing?

The emergence of the middle-class of influencers is not something I anticipated. This hit home a month or two ago for me, personally. I don't recall if I've posted it here or on a different comment section, so apologies if I'm repeating myself, but at the BJJ/MMA gym I train at a young guy came in looking a like a Wish version of a Paul brother, along with his entourage/camera guys, I guess to film some sort of post for socials. We were kind of laughing it off, but it turns out the guy has something like 2.5 million followers on IG and 5 million on YT, and I have not ever heard of him....me, who is internet-gremlin-brained enough that I pay good American dollars for this substack.